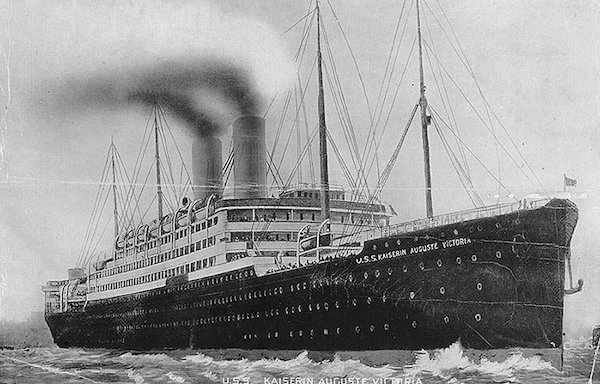

S.S. Kaiserin Auguste Victoria

USA immigration is a focus because of the exceptional record available online of the substantial numbers of Lika people who migrated to the USA from the 1890s to the start of World War 1 (WW1). Immigration continued after the end of WW1 but not at the same rate and there is smaller peak again following WW2 from the late 1940s to early 1950s and mainly from allied displaced persons camps in Germany.

A project has been initiated to record all Lika travellers before 1921. The information is available on multiple websites but many details are incorrectly transcribed including surnames and village of origin, making it very difficult to discover ancestors. A database will be made available on the website in the future. In the meantime some basic analysis of the collated data can be viewed on this page.

Examples

Examples are provided to high-light some of the issues in researching Lika migrants. Each example has a different focus amongst the many common challenges.

| Key Surnames | Focus |

|---|---|

| Borić, Borčić | Change to another valid Lika surname when in Utah, trying to make sense of mangled surnames and how to go about discovering village of origin. |

| Vukmirović, Tonković | Dealing with contradictory person details with a surname change |

| Zjača / Zjačić | Name change to Miller when in Utah, including a gruesome incident in Bingham, Highland Boy |

Village Summaries

Immigrant details from the manifests are listed by village and will be added to progressively as more records are discovered. The below table has links to initial research for each listed village. For those who stayed in the USA a further linked paged will be developed to capture further USA information.

| Village | Notes, Surnames |

|---|---|

| Frkašić | 18 immigration records and 4 USA records Adžić, Ćupurdija, Ivanišević, Klašnja, Koruga, Prica, Tišma, Žigić |

| Kozjan | 16 immigration and 2 naturalisation records Hinić, Knežević, Svilar |

| Medak | 13 immigration, 4 naturalisation records Bruić, Crnokrak, Lasković, Maoduš, Mihić, Oklopdžija, Potrebić, Uzelac, Vlaisavljević |

| Pećani | 48 immigration records Budisavljević, Dozet, Mandić (Jošani) Manikosa,Svilar |

Migration Overview

There are multiple online resources for shipping manifest lists during the pre-WW1 period. The key websites are http://www.ancestry.com and http://www.myheritage.com both of which charge for access, and http://www.familysearch.org which is a free resource. The latter is a subset of the Ancestry/Myheritage records perhaps around 75% so a good place to start.

There are obvious gaps in the online manifest records and it is impossible to know the percentage of missing manifests. Undoubtedly some original manifest pages were lost across the thousands of sailings to the USA. At some point the original paper manifests were captured on microfiche. The aforementioned websites used the microfiche record but there is no information as to the percentage of the microfiche record that has been transcribed.

The majority of migrants before WW1 were born between 1860 and 1895 and depending on the type of ships manifests included their nearest relative in place of origin and the person they were travelling to in the USA and their relationship to them. In the latter case it is difficult to be certain of the stated relationships.

In addition to the ship manifests, USA authorities have digitised multiple types of other records. For Lika people who stayed permanently in the USA there’s a good chance of finding their trail and descendants. In additional to the above websites, other resources are available for research, however, given the popularity of genealogy in the USA, most of the websites charge for access including most registry offices.

There are very few records of return travel to Europe. Either the manifests no longer exist or they haven’t been digitised. Those available are very basic, typically listing only the name of the traveller. In addition, it appears that the Austrian Empire did not keep any records of rural folk leaving and entering its territory.

Migration in Context

The main reasons for this mass migration were; earn money and return, escape the poverty and hardship of Lika, avoid Austrian army conscription or to flee familial issues. On arrival the vast majority of males found themselves in the burgeoning primary industries; mining (mainly coal and metal ores), iron & steel production and downstream heavy industry. Consequently, a sizeable minority perished in the workplace or from health issues resulting directly from the work environment. In mining areas, tunnel collapses underground left miners buried permanently and in some cases never identified.

The destination in the USA seems to have been based on the village of origin, for example, people from the Gacka valley typically travelled to Cleveland, Ohio, those from the Korenica area typically went to Chicago and those from across the county border in western Kordun generally travelled to Pittsburgh and close-by Steubenville. Of course, many followed to where the first migrants had settled. During the peak migration period the vast majority of migrants travelled to a family member or friend from the same or nearby village. Chicago was by far the most popular initial destination, but from there many went elsewhere to find jobs, mainly in mining; Chisholm & Hibbing in Minnesota (the Iron Range), Salt Lake area mines, Butte Montana, Pueblo Colorado etc.

Changing names and surnames in the USA

Very quickly, migrants adopted local christian names. Some took direct equivalents such as George (Đorđe), Stevan/Stephen (Stevan, Stefan), Pete (Petar), John (Jovan), Sophie (Sofija), Helen (Jelena), Dan (Dane, Danilo, Daniel), others a close match such as Eli (Ilija), George (Đuro), while others still adopted a generic Mike or Mary for just about any Lika name beginning with M. Some took totally unrelated names.

Within the migrant generation surnames started to change depending on the complexity of the Lika surnames. Surnames without slavic characters or rolled ‘r’s tended to remain the same for example, Brakus, Svilar, Studen. Surnames ending in ‘ć’ were replaced by ch, so Hinić became Hinich. Names with ‘č, š or ž’ at any point in the name were replaced by ch, sh, zh or simply dropped, for example Žigić became Zigich. Some surnames with a ‘J’ were changed using ‘Y’ giving close approximation to the slavic sound. Of course there were many variations to the above, for example, Hinić also changed to Enich across a number of families. A few adopted a totally different name, making it near impossible to trace them through the USA record, for example, the English ‘Miller’ was a popular adopted surname whereas others adopted other slavic or Lika surnames for no obvious reason; Borich instead of Borčić and Devich instead of Drakulić.

Adding to the confusion

On arrival (before 1914) Lika Serb migrants were listed as Austrian, Croatian, Hungarian or even Serbian, although technically they were all Austrian. In USA census records, as well as the previous nationalities, Slovenian and Slovene were also stated.

A migrant’s place of origin on some documents can be misleading, for example, instead of giving their actual village of birth, the nearest larger village or town was stated. Another issue is that some Lika hamlets have disappeared from the map and without detail local knowledge the name on the manifest will be meaningless. This is particularly true of hamlets named after surnames. Of course misspellings of place names were also common to the point of being indecipherable. Most Lika migrants were illiterate or at best had limited schooling and therefore many names were written down by someone else based on what it sounded like to them and the scribe likely to have be Italian, French or German depending on the port of departure.

With respect to relationships, the south slavs have no word for ‘cousin’ instead each such relation is a brother or sister and then qualified e.g. brother by an aunt. In most early immigration records the word ‘brother’ is written even though the passenger’s surname does not match the person’s surname he is travelling to and so at best they were cousins. As the years passed, the immigrants learned to use ‘cousin’. Along similar lines; the word ‘Uncle’ on manifests could have been given to mean the uncle of the traveller’s spouse and for a married women her stated ‘father or mother’ could actually be her husband’s parent as she would have been living in their farmhouse before travelling to the USA.

In spite of all these complications the USA record provides substantial information that can be used to trace ancestors to their village of origin as well as their descendants in the USA.

Ports of Departure and Arrival

By far the closest and presumably the easiest port to reach was Trieste (in the Austrian Empire at this time, now in Italy) and a little closer the port of Fiume (present day Rijeka in Croatia). The issue with both ports was the extended travel time to the USA as the ship had to sail down the Adriatic, across the Mediterranean and up the Atlantic coast to typically French and British ports to pick up more travellers. The German ports of Bremen and Hamburg were also commonly used and while they involved a longer journey and some cost to get there, the time on ship to New York was substantially less.

The journey to Bremen, for example, had to be by train, which itself would likely take a few days. The town of Ogulin, which is very close to the north east Lika border, was the likely place of departure with its railway connection to Zagreb and access to the major rail routes across central Europe and Bremen. Fiume was also linked to Europe by rail. The extension from Ogulin to Vrhovine and on to southern Lika was seemingly only available from around the start of World War 1 in 1914 (precise details to be confirmed). While Ogulin was also connected to Fiume, it doesn’t seem to make much sense that travellers would use the train unless they came from villages relatively near to Ogulin. However, for ship departures from Trieste, a train from Ogulin would have shortened the travel time. For southern and western Lika travellers, going to any number of small ports on the Dalmatian coast would have likely been the quickest way to Fiume and Trieste, although it is possible ships from these ports to the USA may have stopped off at for example, Spalato (present day Split).

Other common ports of departure in the manifests included Le Havre in France, Rotterdam in Holland and Southampton and Liverpool in the UK. Assuming these ports were starting points, Lika travellers had to change ships also.

The most common port of arrival was New York (Ellis Island), however, Baltimore was a key port of arrival particularly for ships arriving from German ports and less so Boston and Philadelphia. Some even travelled via Canada, either to work there or as alternative route to reach the USA great lakes cities.

Ship Manifests

There’s no evidence that Austrian authorities kept any record of people leaving the empire for other lands, particularly poor farmers from a backwoods region like Lika. Nor did any other European countries it seems check travellers on trains across their borders. Lika migrants almost certainly did not have identity papers. By effect, therefore, the ship manifest and perhaps a note of the name and address of a person already in the USA represented the only form of identity for entry in to the USA.

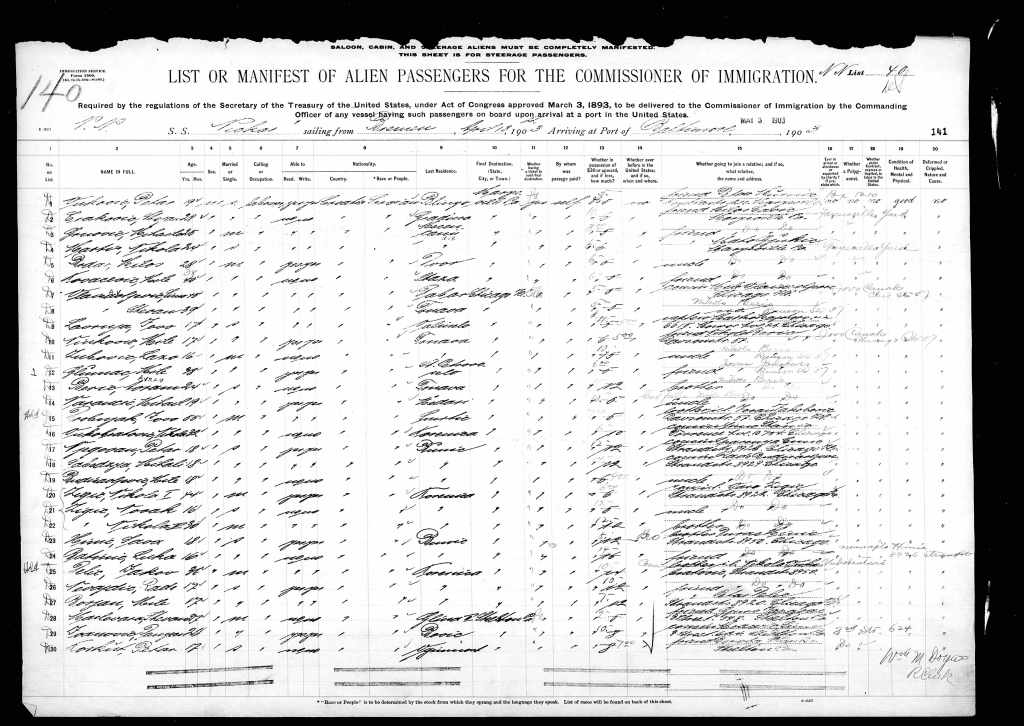

The manifest was completed at the port of departure, presumably on payment of the fare. The USA authorities specified the information to be collected. The manifest forms varied but there were two main variants . The 1-page form collected basic information about the traveller (name, age, marriage status, occupation, place of residence) and the name, address and relationship of the person they were travelling to in the USA. The 2-page form additionally included the name, address and relationship to a person in the travellers’ place of origin and some physical characteristics.

The addresses for Chicago and Cleveland for example were in the main limited to a handful of numbered properties, presumably tenements. The main streets in Chicago were The Strand, Torrence Ave and Green Bay Ave and in Cleveland, Hamilton and St Clair.

The manifest to the left is a fairly typical example, just about readable but without any knowledge of Lika villages and surnames it’s difficult to make out the details.

Click on the image to see a larger version.

On arrival in the USA, the immigration officials would use the manifest as a check sheet and on some manifests there is additional writing to correct details, typically in relation to the destination person/address. The immigration officials could hold migrants for a variety of reasons, for example, health check, and for many women there was check of the destination and the means to arrive safely. Sometimes this resulted in being held for a number of days until communication was received from the destination person. The officials also had the power to deny entry to the USA although it’s not certain what criteria were used to determine admittance or refusal. Some sheets have stamps that say ‘admitted’ or ‘deported’ but they tend to be in the minority as it seems it was not common practice to stamp the manifest.

Other Sources of Information

The large number of USA record types that are available online is a goldmine for researching Lika migrants and their descendants in the USA. The key record types are: i) USA census records up to 1900 to 1950. In 1900, migrants were mainly living in work camps, census records for 1910, 20, 30 include the immigration year, although many of those researched were not accurate. 1950 census records were added from 1st April 2022. ii) Birth, deaths and marriage certificates, iii) newspaper articles and obituaries, iv) Military draft records for WW1 & WW2, v) Naturalisation applications, vi) City/town directories particularly useful for smaller populations centres. Each record can possibly add a small piece of additional information, particularly if the manifest is not available on original entrance to the USA.